For nearly as long as I’ve been taking pictures, I’ve loved photographing loons. They have offered countless hours of joy behind the lens, taught me lessons about photography and ecology, and helped me find weaknesses in the cameras I’ve spent my career evaluating. The Common Loon Is Truly An Uncommon Bird In Maine, and throughout the eastern part of North America, “loon” refers to the common loon (Gavia immer), although there are other species of loon. The common loon, also known as the great northern diver in Eurasia, part of its non-breeding range, averages around 28 inches long (0.7 meters) with a wingspan of up to five feet (1.27 meters). A common loon (Gavia immer) swims on a small Maine pond in mid-April, 2024, a few weeks after arriving inland from the Atlantic Ocean. This older image of a loon spreading its wings, a common part of its regular preening process, shows the bird’s sizable wingspan. They are also unusually heavy birds, weighing an average of nine pounds (4.1 kilograms). A healthy adult male loon can weigh up to 14 pounds (6.4 kilograms). For reference, this is a very similar weight range as an adult bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), which has nearly twice the wingspan of an average loon. This bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) is a bird of prey common to Maine ponds, lakes, rivers, and the ocean. Thanks to stronger environmental protections, the bald eagle population in Maine has increased significantly in the past 50 years. In 1972, there were an estimated 29 nesting pairs in Maine, down from more than 1,000 in the prior century. In 2018, during a regular survey, there were more around 800 nesting pairs — more than the total number in the entire United States when the bird was declared endangered in 1972. It is fantastic news for the ecosystem at large, but not great news for loon chicks.

A big reason for the loon’s density is its bones. While most birds have hollow bones, many of a loon’s skeletal structure comprises solid bones. These make the birds less buoyant and make them more proficient swimmers and divers. Unsurprisingly, this aquatic adaptation makes loons especially clumsy on land, so they are very rarely seen walking. They are exceptional fliers, though, despite their weight — averaging flight speeds around 75 miles per hour (121 kilometers per hour) during migration. Clumsy on land, the common loon is an excellent swimmer, unparalleled diver, and very adept flier. Their Haunting Call Heralds the Changing Seasons Speaking of migration, part of what makes the common loon such an iconic part of life in Maine is how its appearance coincides with the seasons. Both in terms of its plumage and literally when it is seen on lakes and ponds, with the changing seasons, so too does the loon change. One of the most reliable signs of spring is loons returning to inland waters, filling the crisp dawn and dusk air with their distinct, haunting song. As the birds nest and try to raise their young against daunting odds through the summer, their dulling feathers signal that winter’s arrival is just around the corner. If the young survive, they will stay a bit longer than their parents, but by the time first snow hits, they too have made their way toward the coast, seeking water that won’t freeze over. This year, the loons arrived a little early — it was an especially early ice out in Maine — but that didn’t mean that winter was totally over. It is very unusual to see a loon in a snowstorm on inland water. In fact, in 15-plus years, my dad has never gotten photos of loons during a snowstorm.

This rhythmic annual cycle also means a lot to me, personally, as “loon season” means that wildlife photography opportunities are slated to significantly increase. Winter in Maine has its charms, but by the time March and April roll around, I’m ready for it to end. The dreary grays and browns give way to neon greens and yellows, and the animals reappear. It doesn’t get much better. What I’m Doing: Part Documenting, Part Teaching, and Mostly Learning That brings me to today and this new series that will follow the photos and stories of a small Maine pond. While the focus will primarily be on the loons that live there — a family my father and I have photographed for many summers — I will also look at the other ways in which the pond evolves and other critters that call it home. The great blue heron (Ardea herodias) is a very photogenic wading bird that we occasionally see at the ponds we frequent. It lives in most of North America, and there are different subspecies, which look very similar, located in specific parts of North America. There is even a subspecies, A. h. cognata, that lives in the Galápagos Islands. I can’t personally see a difference between them, but I’m not an ornithologist. Much like the animals on the pond, this series will grow and change in unforeseen ways. It will primarily serve as a living document, published every week or two until the loons make their way east to the Atlantic Ocean. Canada goose (Branta canadensis) is another sign that spring has arrived. They don’t all stick around for the summer, but it’s not unusual to see dozens, if not hundreds, during a spring paddle in Maine. While I intend to do quite a bit of shooting myself when I’m back in Maine, I will rely on my father, Bruce, for many of the photos for this series. I count myself as a reasonably dedicated photographer, willing to get up at obscene hours to get good shots, but my dad is probably the hardest-working person I know, and that carries over to photography in spades.

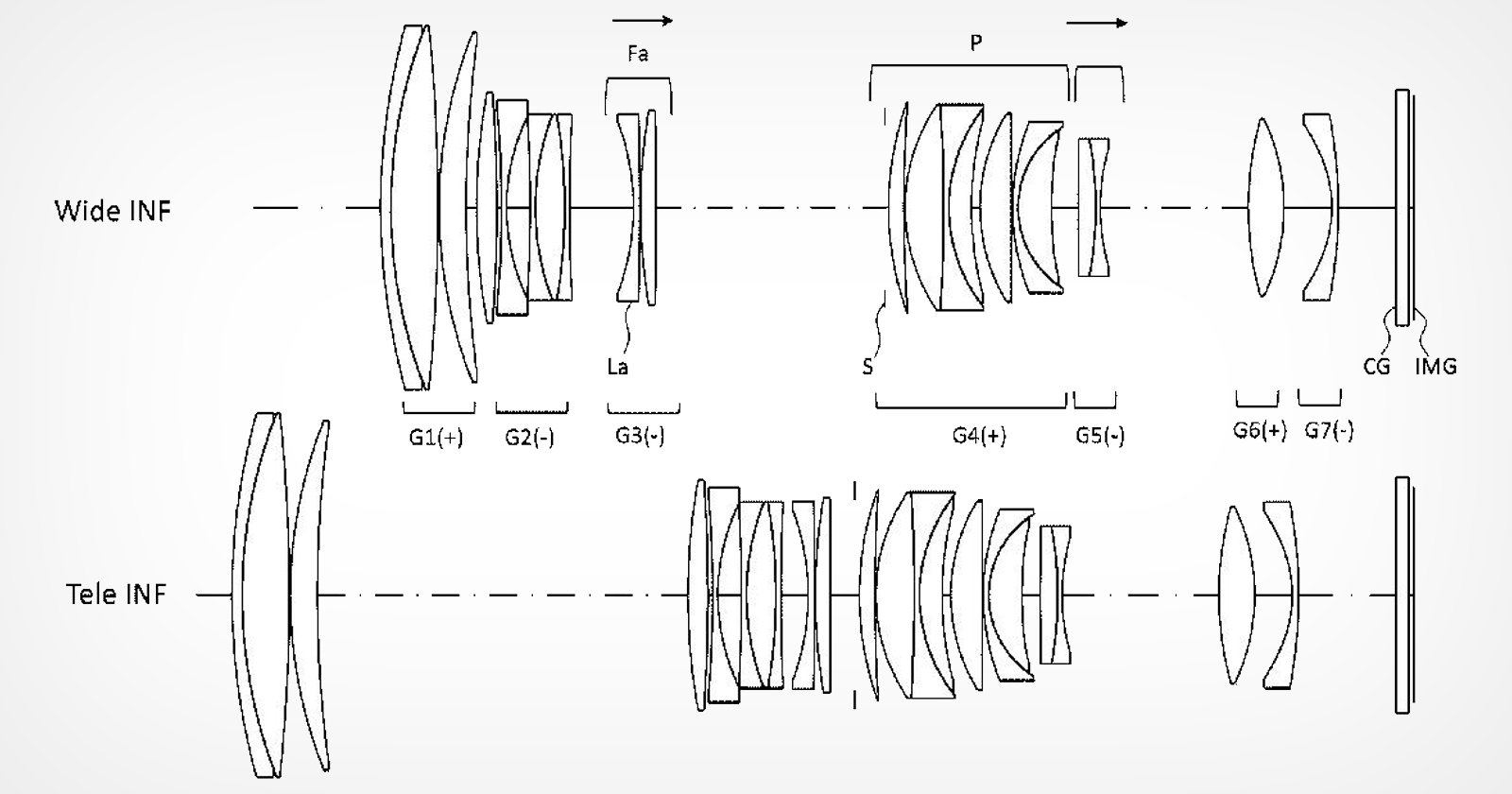

My fingers are crossed that the series will be able to follow a pair of loon chicks from hatching until their first migration in the fall, but a baby loon’s existence is a treacherous one. This is one of my favorite loon photos from my archive. Unfortunately, we had just a couple of days to see both chicks. However, one of them did survive to migrate in the fall, which is an unusual achievement. If a breeding pair makes a nest and lays eggs, which is to be expected, there will be just one or two eggs in the clutch. Due to risks to the nest, general difficulties with incubation, and a high volume of predators once a loon chick hatches, the average pair raises one chick to fledge every other year. The odds are not in their favor, unfortunately. I desperately hope I won’t have to write that article in a couple of months. No matter what happens, this project will provide ample opportunity to discuss biology, ethology, conservation, and photography — including tips for shooting from a kayak and dialing in the right exposure and focus settings for photographing loons. Their black and white plumage is a real bugbear for even the best cameras. The Series Will Be Shot on an OM-1 Mark II Speaking of cameras, the series will also be a long-term and somewhat disorganized test of the OM System OM-1 Mark II with an assortment of OM System lenses, especially the new 150-600mm f/5-6.3 IS, the longest Micro Four Thirds lens on the market. Although we will be looking at a couple of ponds and related waterways throughout this series, these two loons will be the primary subjects. Loons are monogamous birds, although they rarely, if ever, mate for life. A breeding pair can stay together for five to seven years, on average. These two loons were successful parents last year, so my fingers are crossed for a repeat success.

The newly-arrived loons are certainly eating well — if not a bit messily — so far this spring. While I hope to share useful information for fellow wildlife photography enthusiasts based on hundreds, if not thousands, of hours taking pictures on ponds, I also expect that researching different topics will teach me quite a bit about loons and the other animals I love so much. See you next time, when I’ll focus on ethical and responsible wildlife photography, including tips on using long lenses and understanding suitable viewing distances to always keep animals safe and undisturbed. Image credits: Photos by Jeremy Gray and Bruce Gray